Tom Brady’s Dark, Glorious American Dream

Because we’re millennial sports fans who grew up in suburban New England, few subjects have unified my hometown group chat like Tom Brady, whose Patriots career was a constant in our lives from ages ten to thirty. When Tom won, it felt like we did too. But over the past few years — even before he left for Tampa Bay — Tom began to polarize the chat.

“Very torn about this game,” one friend texted of Brady’s first game against the Patriots. “Want the Pats to turn things around but also want to drink the tears of the Tom haters.”

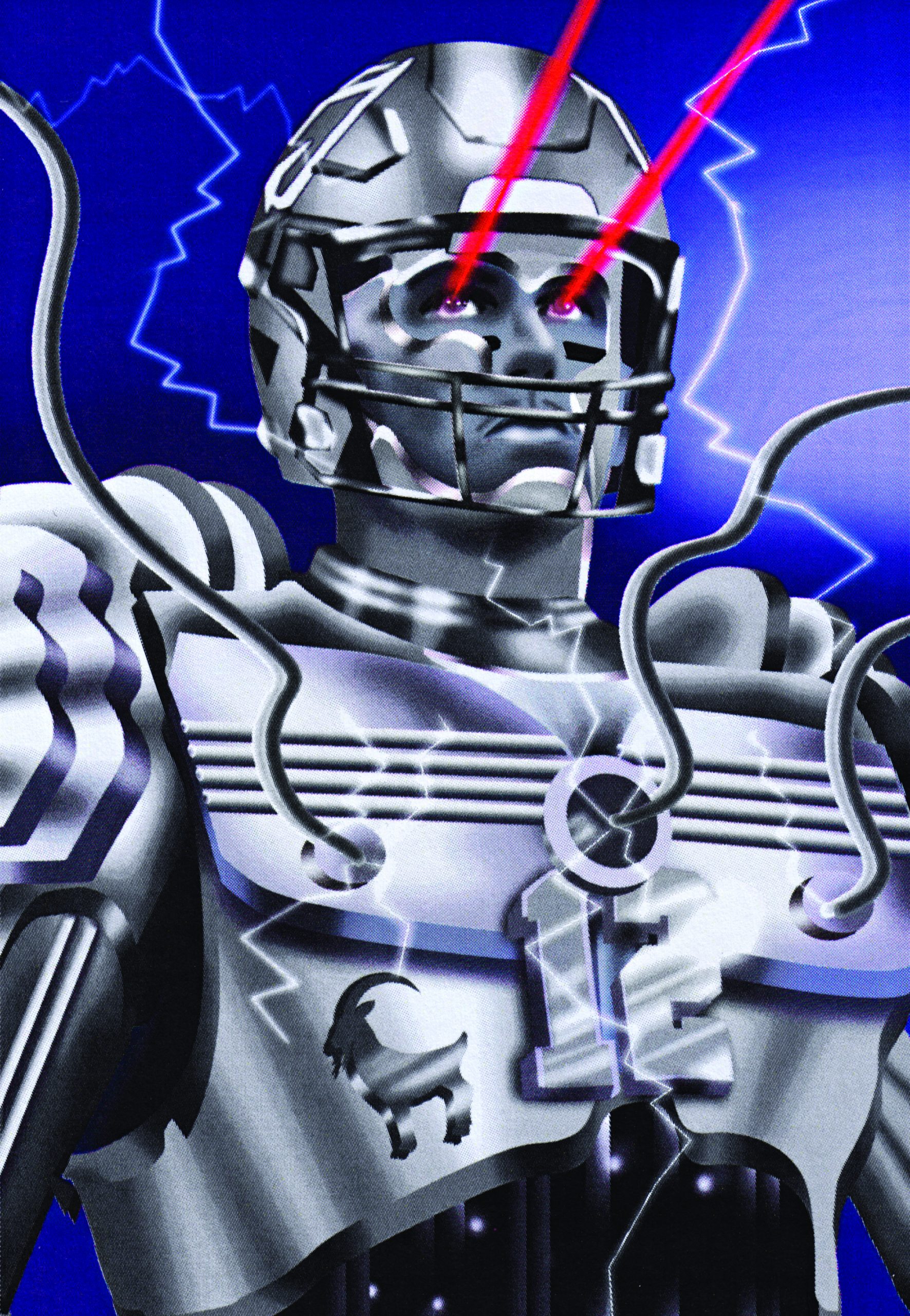

“Tom is insufferable,” another wrote. “It feels like in comics where the superhero becomes the dark version of themselves and is twice as powerful.”

I agree that there seems to be a dark-arts quality about the quarterback these days. We’re running out ways to explain his career that don’t include barter with the devil. What happened to Tom Brady?

It’s dusk in Tampa, and Brady is at the wheel of his Bugatti Veyron, cruising to his $29M bayfront estate from Raymond James Stadium, where he spent the afternoon laser-blasting the Chicago Bears, 38-3, and founding the 600 TD club, a threshold no one else may ever reach. His lithe body is swathed in custom fabrics, sinewy hands and gaunt face tanned by the Floridian sun. At home he’ll be greeted by his bright, smiling offspring and luminous wife, who, in addition to being considered one of the world’s most beautiful women, is also twice as rich as him. Palm trees strobe past a darkening sky. Life is good, but Brady is ripshit pissed.

“FIFTY FUCKING POINTS!” he fumes. “It was right there to have! How did we not score fifty?!”

“G@DD@MN C@CKSUCKING M@THER@CKER!!!”

It’s a good question. At the absurd, breathlessly cited age of 44, Brady has three more championships than the next-closest guy on the list, and he owns the career passing yards and touchdown marks, the two most prestigious records for his position. He’s the consensus Greatest of All Time quarterback in a culture pathologically obsessed with the distinction of individual greatness, and his resume gets him an interview for greatest American athlete period — up there with Jordan and Tiger, Serena and Phelps.

Still, Brady isn’t satisfied. To this day, he famously practices, prepares, and competes like an undrafted rookie on a non-guaranteed contract. An ad campaign for Hertz’s new fleet of rental Teslas features Brady plugged into a charging port — the joke being he’s a robot.

“The reality is that I’m very human,” Brady insists in a recent interview, which is exactly what a robot would say.

It’s not just Brady’s play that that seems immortal. A heavily-upvoted tile-collage posted to Reddit with the caption “I think Tom Brady may be a vampire” compares the QB’s team headshots across the years. His face does appear to change, but not from age. He morphs from a sort of doughy, goofy (but still handsome) 20-something with a bad haircut into a sentient Ken doll — lineless and gaunt and eerily symmetrical.

The game for Brady seems to have shifted. As the title of his 2018 docuseries, Tom vs. Time, suggests, this is about more than winning football games. Like some power-hungry villain in a cautionary myth, it seems that Tom Brady wants to live forever. Brady’s ruthless ambition is fetishized by fans and media alike, but it’s getting increasingly cringe and unrelatable to an alienating degree — at least among my friends. How is he doing it? And what’s this guy’s deal? It seems that Brady doesn’t think he’s very good, and he’s haunted by the life he narrowly avoided.

To the question of how: Brady has co-signed a whole book, available in paperback on his website for $20.00 USD, that details his preferred answer. He’s built an entire health coaching/fitness gadget business on the bet that we’ll buy his story — that his freakish longevity and youthful sheen are thanks to a cutting-edge health and wellness regimen that includes eating lots of vegetables, drinking plenty of water, doing fitness band workouts, receiving frequent massages, and — you might want to sit down for this — getting a good night’s sleep.

“I don’t think my body’s going to give out. I really don’t.”

No doubt these things have helped. But Brady’s formula is mostly common sense, and it’s hard to believe that his peers, fellow elite contestants in the sport equivalent of Squid Game, aren’t taking basic care of their bodies too. There must be more to the story.

Many have pointed to Brady’s relative injury luck — but relative is the operative term here. Upon inspection, Brady’s medical record looks like a script for Saw 10. The first half of his career was plagued by chronic issues to his throwing shoulder, which he had surgically repaired in 2004, and for which he spent a cumulative 116 weeks on the injury report. The famous 2008 ACL tear that robbed him of the chance to avenge 18-1 has kept his left knee in a brace ever since. He’s broken his right foot in two places, lacerated his right hand, and, as of a 2020 survey by ESPN, amassed 152 weeks listed as injured for 16 different body parts.

In May 2021, it was reported that Brady won his seventh ring on a torn meniscus, which he repaired with offseason surgery. And that’s just what got reported. Brady told Howard stern that he played the 2005 AFC Championship Game with a sports hernia that caused his testicle to swell to the size of an orange. Who knows how many undocumented concussions he’s sustained?

Still, Brady belligerently asserts that his body will carry him as far as he wishes. “It’s not going to be physical,” he recently predicted of his eventual retirement. “I don’t think my body’s going to give out. I really don’t.”

To address the elephant in the room: Because football is an especially violent game and viewership hinges on star players’ health, the NFL is notoriously lenient on the issue of performance enhancing substances, so it has a vested interest in doing things like notifying players of their testing dates far enough in advance that they can get clean in time to pass. There’s precedent for stories of star players linked to illegal substances being magically swept under the rug — Ray Lewis’ 2012 dalliance with deer antler spray, the 2015 HGH shipment that Peyton Manning blamed on his wife. Julian Edelman, Brady’s close friend and summer training partner at the QB’s remote Montana hideaway, was less lucky, but still pretty lucky; he received a PED suspension in 2018, a four-game wrist-slap that paid off with fresh, roid-infused legs later that season for a Super Bowl MVP trophy.

It’s entirely possible that Brady cycles in the offseason to stay on top of his game; in a sport so harshly competitive, who could blame him? But this amounts to speculative rumormongering. There’s no off-the-field smoking gun. The answer seems to be a matter of skepticism, and it comes down to how cynical you are about the winners in the game of American success.

There’s an easy but rarely made argument that pound-for-pound, Tom Brady is NOT the GOAT QB. His rivals uniformly outrank him across major rate-based indicators. Peyton has 5 League MVP awards to Brady’s 3 (though Brady may gain a notch this year). The single season passing TD record is Peyton’s, not Brady’s. Both Peyton and Brees have thrown for more yards in a single season than Brady, and both have greater career per-attempt yardage and touchdown figures. Brady is 20th in career completion percentage, 25th in touchdown percentage, and 29th in yards per pass attempt. At the level of the single pass, game, season, or even stretch of multiple years, there have been better QBs. What’s allowed Brady separation — apart from the size of his trophy case, of course — is sheer time. Maybe a part of him knows this.

“If you wait by the river long enough, the bodies of your enemies will float by,” writes the Ancient Chinese writer and general Sun Tzu in his military treatise, “The Art of War,” a known source of inspiration for the Belichick-Brady Patriots. Brady is the undisputed GOAT of waiting by the river.

A theory: Tom Brady is the less the product of his special body or technique than the inevitable outcome of a culture obsessed with creating him: the death cult of American success, which always finds and anoints a winner. If that sounds extreme, here’s Brady himself, salivating over the rigors of the NFL season:

“It weeds the people out. It weeds the weak-minded out. It weeds the physically weak out. The tough guys rise up.”

Brady would know. There’s a whole documentary about how he almost never got a shot to play in the league, “The Brady Six,” named for the six quarterbacks selected before him in the 2000 draft, and the round he was finally picked. In a now-famous interview shot, Brady wipes away tears as he recalls finally being taken at pick 199. The image has been gleefully immortalized in memes by his anti-fans, but lost in the spectacle of Crying Tom Brady are the words he speaks in that moment:

“I was like, ‘I don’t have to be an insurance salesman!’”

He frames his excitement in negative terms, exulting not in the job he got, but the one he narrowly avoided. Part of being picked, for Brady — part of high-status success for anyone in any domain of our world — is the powerful relief that comes with the chance to spend your life doing something you actually enjoy. This is rarely talked about, because it’s both obvious and painful: how few of us get to obey the old wisdom to “do what you love”, forced instead to sell our time in exchange for the right to live.

The Brady Six takes the implicit position that Tom Brady is Goodness and Rightness incarnate, reducing the six QBs taken before him to punchlines in his conquering legend. A favorite target is Giovanni Carmazzi who, despite going three rounds before Brady, never started an NFL game. “Givoanni Carmazzi does not own a television,” the narrator coolly reports. “He describes himself as a yoga-exercising farmer.” The camera frames a long close-up of a goat chewing on cud. “He has five goats.” The message is clear: Because he took his small football fortune and went to live in the country, thus betraying the sacrosanct assumption that winning NFL games is the meaning of life, and because he doesn’t watch TV, Gio Carmazzi is a loser who deserves to be ridiculed. Brady is the GOAT; Carmazzi herds them.

Sports media uniformly accepts this view, but in reality, there’s no value difference between being a seven-time Super Bowl Champ and a goat-farming yogi. If anything, it’s easier to argue that Brady’s life path, with its high-carbon yacht-and-mansion lifestyle, is a worthier subject for criticism than Carmazzi’s quiet, low-impact existence.

Rather than exceptional virtue, Brady’s relentless workaholic perfectionism seems to stem from a deep sense of insecurity:

“I was a backup quarterback on an 0-7 freshman team. I was seventh on the depth chart at Michigan. I was the 199th pick and the fourth-string quarterback for the Patriots,” Brady explains. “And I know there’s someone out there that’s trying to take my job. And I always said, ‘if I ever get a shot in pro football, I’m never getting off that field.’”

Maybe Brady’s career owes as much to his internal qualities as the external forces that shaped them, and far from God’s most special boy, Brady is the predictable output of a cutthroat algorithm that rewards the darkest impulses of the American psyche: ruthlessness, domination, winning at all costs.

This, I think, is the real tragedy of Brady’s public persona: Because the specific fear of losing your job (and the general fear of inadequacy it connects to) is almost universally relatable in our social order, Brady could have been a much more relatable, humane figure to many people — an humanitarian icon in the mold of Ali or Abdul-Jabaar. Instead, the QB espouses a partial, narrowly self-interested worldview, as in a recent interview with Jim Grey, parroting simplistic “bootstraps” rhetoric about personal responsibility. Even though Brady can’t forget that he was this close to being just like everyone else, it seems he can’t remember it either.

All of which would perhaps be fine if the stakes of Brady’s career were confined to the NFL stadium. Football is, after all, just a game — one I can’t help but love. There’s no doubt that Brady is a master craftsman in the mold of the Shokunin, and that the way he plays quarterback — the acuity of his mind, the grace of his form — is sport transcending to art. And it’s clear, from watching Brady, that he takes a beautiful joy in football, assuming the monk-like wisdom of children at play. My friends and I will always respect and remember fondly this aspect of who Brady is.

But his influence isn’t limited to football, because the cult of celebrity has lavished Brady with a fortune he’s determined to grow; enough is never enough. In a recent press release disguised as a Wall Street Journal profile, Brady announces his next business venture, an eponymous sportswear label that aspires to be “the finest sports brand in the world.” Because what the world needs right now is more athleisure. In the years to come, Brady’s fortune will doubtless compound. Contrary to past comments decrying processed foods as “poison for kids,” Brady now takes checks from Subway, whose subs an Irish court recently determined are too sugary to qualify as bread. He’s now a Musk-like booster of cryptocurrencies and NFTs, poetically symbolized by his new Twitter avatar: Brady’s face with laser eyes. The image surely hews closer to the truth than he’s aware.

"Stranger things have already happened."

There’s a very possible alternate universe where Tom Brady became an insurance salesman and was forced to endure the quiet, unglamorous triumphs and humiliations of the lives of us mere mortals. In an equally likely other world, given what we know of his associations, Brady becomes next in the line of celebrity puppets for an ideological apparatus that seeks to replicate the brutality of football in the broader world. Some quick arithmetic: Let’s say Brady plays five more years, then builds his influence for another decade more. That puts us at…Brady 2036: Make America GOAT Again. Stranger things have already happened.

I guess what I’m trying to say is maybe we should praise winners a little bit less and uplift losers a little bit more. Maybe we should be a little less cutthroat, and a little more kind. Maybe if rather than entertainers or athletes, we glorified, say, goat farmers, we’d live in a world that wasn’t burning. Aside from his undeniable mastery of craft, maybe there isn’t that much to admire in Tom Brady. Maybe he’s painfully human after all.

This article featured in SPIRAL Issue II: Future.